Together with Delta Atelier, we have embarked on a journey of dialogue, exploration and knowledge sharing around the challenge of circular (urban) ports. Explore this journey supported by several working sessions, debates, research and exhibitions in the context of the ‘cultural space’ created by the International Architecture Biennale Rotterdam and its Brussels component You Are Here. While some of the proposed actions were temporary, others have become permanent and tangible.

Changing elements in the transition toward a circular economy

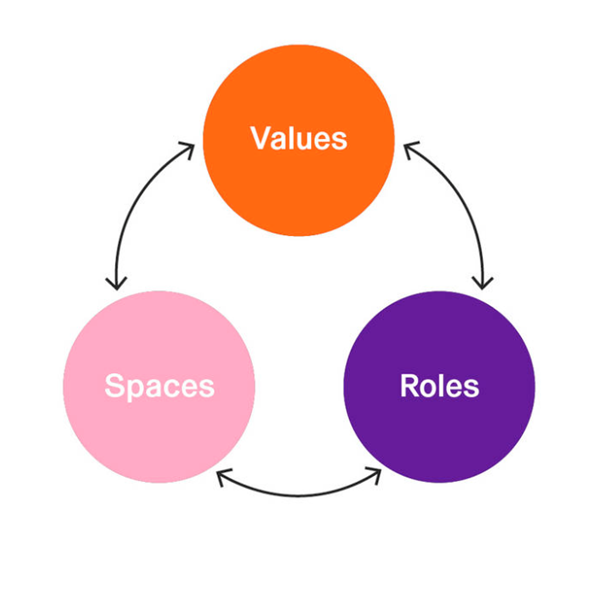

Change is an ongoing process over time. We cannot take one step, make one attempt and call it a day. Twelve insights have been selected and structured around three factors of change: values, roles and spaces. They frame the pathways in which the next steps can be taken to accelerate the transition process.

Three drivers for change

Firstly, the shift to a circular system requires us to rethink the values of our economies in ports and beyond.

At the same time, it also implies a crucial shift in the roles played by the different actors, envisioning a new system of connections and collaborations between ports, cities and regions.

Thirdly, the translation of these progressively mutating elements into a spatial environment needs to take into account how the physical dimension of these dynamics takes place.

Seen from the inside

Take your time for a journey through the various challenges, bottlenecks and boundaries that parties face in becoming first movers in the circular economy. The story is told through the eyes of officials, experts and entrepreneurs working on circularity in port environments. The story is embedded in our 12 guiding pathways, interwoven with eye-opening interviews and statements.

Twelve guiding pathways

The exploration shifted during the process, from merely documenting and collecting knowledge, bundled in the various documents like Lessons Learned, Workbook 1 and Workbook 2, to a more structured approach by initiating strategic thinking and valorising/sharing of insights.

This shifts the focus from looking only at the scale of the ‘City Port’ to looking more generally at existing and potential ‘Circular Port Projects’.

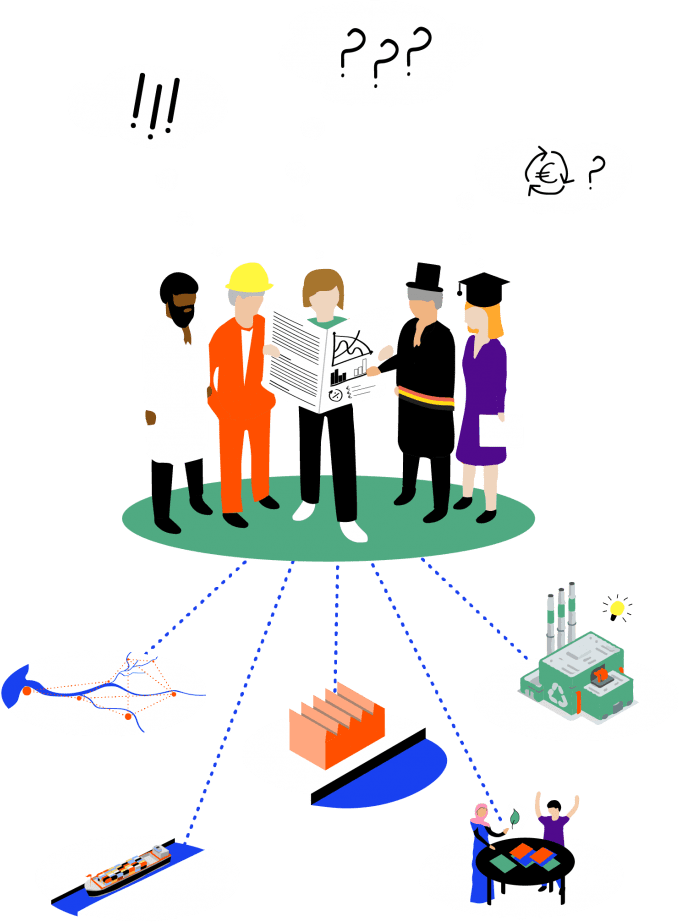

The insights gathered during the Circular (City) Ports process have been compiled and framed within the 3 drivers of change, resulting in 12 pathways that port and government stakeholders can follow to accelerate the transition.

Find out more about the selected pathways below, and about the background of the changing values, roles and spaces in our documentary.

Values in transition

1. Learning from ongoing initiatives to steer future changes

The creation of a tool to monitor innovation on the ground would facilitate the development of a continuous learning process. The innovative practices in the field of circularity active in port areas are in a process of continuous evolution.

Observing practices and tracking their evolution lead to a gradual renewal of the “status quaestionis” regarding the state of transition to circularity in port areas. In fact, it represents, on the one hand, the new knowledge coming directly from the innovative practices and, on the other hand, the new challenges and potentials to be faced during the transition period.

In addition to monitoring the projects, it is equally important to observe the evolution of the ecosystems at port, national and/or European level. All this would lead to the study and discovery of new business models, not only to set up new circular initiatives, but also to steer the entire functioning of ports and related practices in the system. It is crucial to consider how to translate the collected data into different patterns. It can help build common knowledge and make the complex transition to circularity easier to understand, as well as highlighting the benefits of practices and ports that need to be shared and transparent if they want to achieve a more circular mode of operation. Port authorities could play a role in demanding this transparency from their practices, not just at one point in time, but on a regular basis.

2. Regulating to unlock hidden value and interdependencies

In order for the new economy to compete with the old, the hidden value of circularity should be unlocked, the external costs of the old economy should be internalised, and value chains should be examined more thoroughly. These can range from the unbalanced costs of water, rail and road transport to the benefits of the less carbon-intensive new economy compared to the polluting old industries.

These hidden values and the internationalisation of external costs should be researched, uncovered and implemented through regulation. New types of indicators could emerge from on-the-ground monitoring, where the creation of a set of tools to measure the impact of circularity is crucial. This can start by revising old indicators, such as KPIs, to give them a different basis for measuring the effectiveness of old and new initiatives, but with new kinds of added value. The concept of ‘doughnut economics’ (Kate Raworth) already offers a way of integrating social and environmental parameters.

The constitution of these overarching tools should steer circularity at a general level, overcoming the lock-ins in which first movers are stuck. It is important to note that these hidden values are often long-term in nature, while it is also crucial to formulate short-term solutions. With these short-term solutions, more companies could be convinced to move towards a more circular way of working, if the win-win situation is proven.

3. Supporting new economic models via innovation- steered investments

A crucial stepping stone in this process of change is the creation of a framework that could guide investment to support the first movers and the many different initiatives in the field.

Investment should be smart, supporting projects that anticipate future change or projects that need support to take the risk of experimenting. These investments should create the opportunity and environment where risks can be taken and failures can be made in order to find the right way of working, thus facilitating this ‘grace period’.

Investment in experimentation and innovation practices could also focus on shared infrastructure. Europe has taken a first step towards these innovation-driven investments through the research of Prof. Mariana Mazzucato’s ‘Mission-oriented research and innovation in the European Union: A problem-solving approach to foster innovation-led growth’.

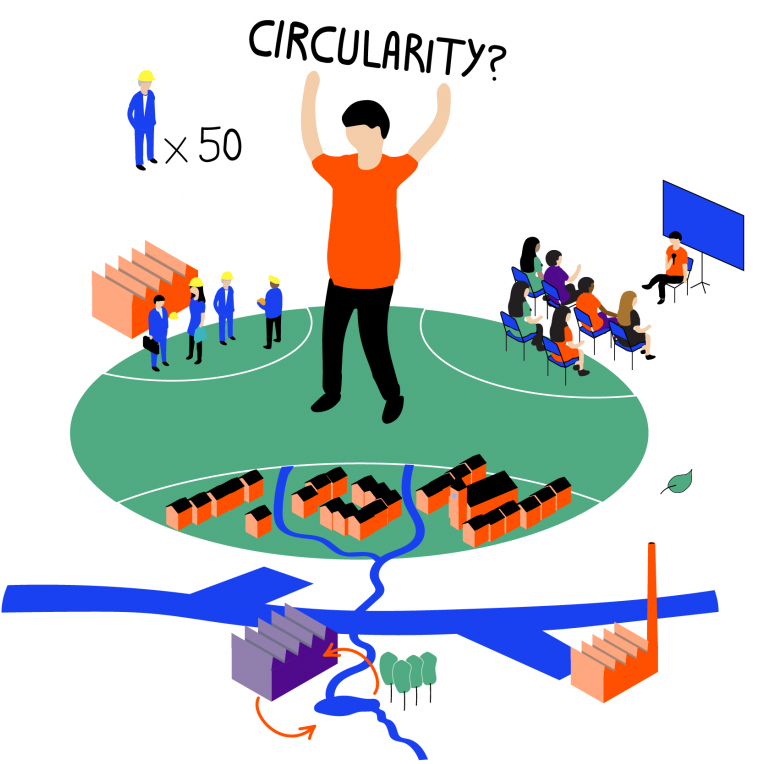

4. Investing in research, training, public awareness and innovation in the field of circularity

Accelerating the transition to a circular economy in port environments means implementing a societal programme for circularity to raise awareness of human capital for this new economy. This should include different engagement and awareness-raising strategies to make the circular economy part of our daily lives, closely intertwined with the different dynamics that come together in our cities.

On the one hand, it will help to clarify the positive impacts that a circular port system can have on the city and the environment. On the other hand, it is also a great opportunity to implement strategies for social issues. Unemployment, low education and other aspects of human capital can find new opportunities in the implementation of a circular system. Therefore, the establishment of educational pathways where cities and ports work together to build employment strategies at city and regional level.

As a public authority, it is important to set a good example to show that it can be done: this is a first step towards this change in behaviour. Furthermore, strategies should be developed to improve the natural environment, not only as a compensatory measure, but also by actively respecting and regenerating it through water management, nature conservation, soil management, etc. The creation of this programme is crucial in order to extend and raise awareness of circularity beyond the borders of the ports. Circularity is a great opportunity to rethink our society, our way of life and our landscape in a more complex environmental logic.

Roles in transition

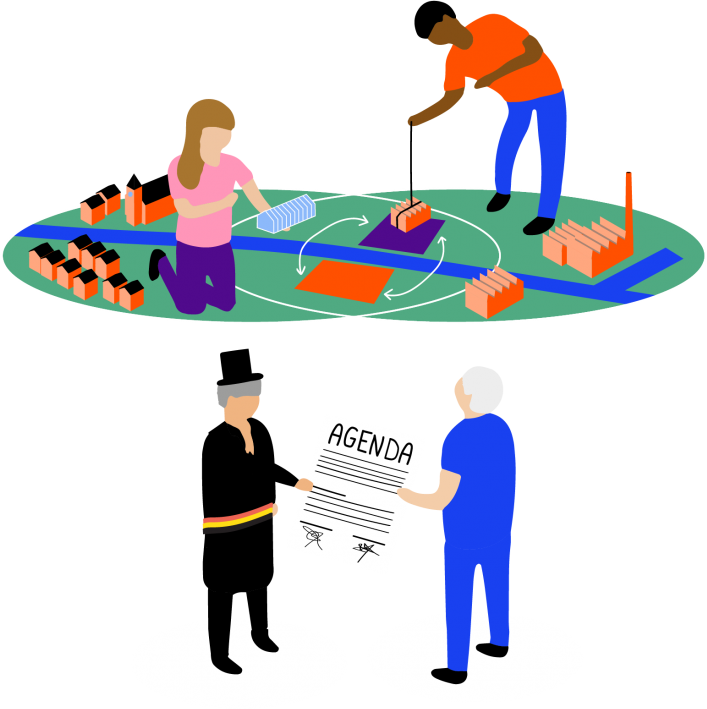

5. Establishing a shared strategic agenda for ports and cities

City and port authorities have the overview and the power to accelerate and steer the necessary systemic change. Strategising around a common agenda is a crucial step in envisioning an overarching circular system where the cooperation and interdependencies of cities and ports guide both new and existing actors.

Both city and port authorities can create a virtuous circle to support the transition by imagining joint actions involving the different communities of practice. In this sense, they can take on a new leadership role as facilitators and initiators of key processes, matching new dynamics with ongoing ones, while constituting specific regulations that avoid lock-ins and facilitate the process of change.

By working together on specific issues, city and port authorities can share legitimacy and be stronger in the economic sphere. Building a common agenda can be an incremental process, where the port and the city can focus on one barrier, one flow, one process, etc. at a time. This gives them the opportunity to take the specific knowledge they need and create a roadmap and business case. Building a common agenda is not only valuable at the graspable scale of ports and cities, but can also be of interest at other scales. Strategies can be developed at the corridor or even delta scale.

6. Building bridges between supra-regional objectives and local opportunities

The appointment of a supra-regional institution improves the operationalisation of European and national legal frameworks in the development of circular port areas. In fact, the constitution of a mediating figure that can manage this change – by guiding and translating certain norms and rules in order to feed the local issues in this transformation process – seems strategically important.

This would facilitate the constitution of specific processes that accompany local actors in the development of a site-specific circular port system. This figure can represent the middle ground where legislation and ambitions find their way through operationalisation at the local level.

The Delta is a valuable scale to work with, where the translation of European goals can be seen in this specific border-crossing region. This mediating figure on the Delta scale will then translate the specific stepping stones of the bigger goals to smaller regions, but can also look for collaborative co-financing at the Delta scale.

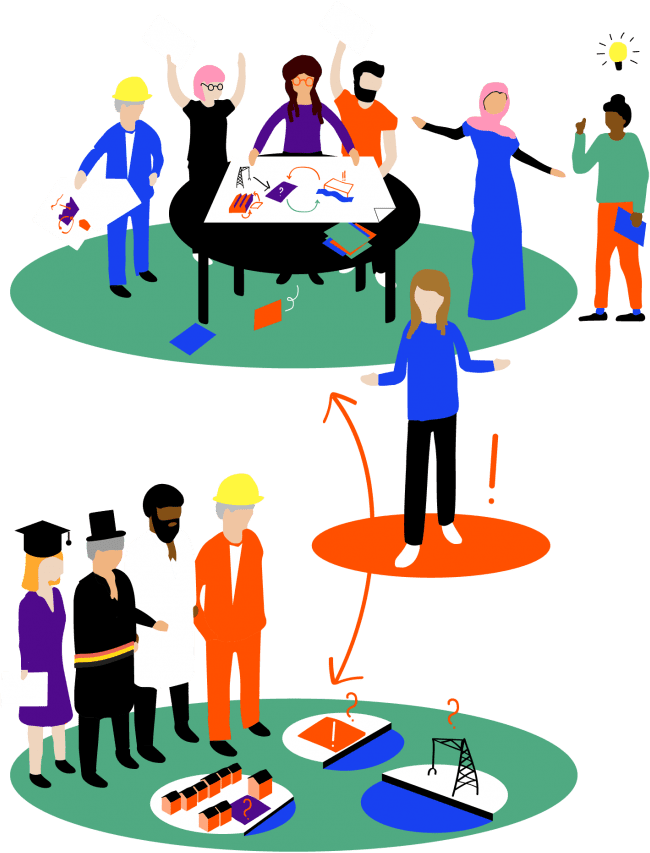

7. Creating a neutral ground for all parties to share, exchange and learn

All parties moving towards a circular system are working in the same parallel directions. This working in isolation should never be considered when envisioning systemic change. It is therefore crucial to create a system of exchange, preferably on the scale of the Delta, in which the knowledge of different practices, knowledge institutions, port authorities and government bodies can be bundled.

The creation of this neutral ground should make it possible to look beyond the existing competition between ports and create a base of support where each actor involved benefits from its presence, cooperation, sharing, etc. From this shared knowledge, a learning process can be constituted to develop new insights on how to advance circularity in the Delta port areas.

Lessons learnt, new technologies, knowledge of innovation and know-how, but also the results of pilot projects and experiments in the field can be brought together in a neutral ground where cross-fertilisation takes place in order to build new mutual knowledge to understand the transition and what the missing links are. Peer-to-peer collaboration can be facilitated by this process, combined with the establishment of tailor-made collaboration programmes, where specific needs and particular qualities come together in the same place, accelerating the process of exchange.

The initiation of different collaborative processes can help to build new circular dynamics and systems within the port areas, extending them to the hinterland and the whole region. This peer-to-peer platform can help initiatives to create new local value chains. At the same time, it can strengthen port-to-port collaboration in the search for a shared programme of exchange and partnership. It can also become a matchmaking platform and a pool of expertise for companies, actors and experts.

8. Launching a dynamic that puts circularity on the agenda and considers the next steps

Launching a dynamic is a way to join forces of different actors, such as experts, leading port authorities, interested public authorities, cross-cutting platforms, etc. It provides a tool for these willing actors to come together and share, strategise and act together, to launch new (systemic) projects, to help build specific coalitions and to put circularity on the agenda of their own and other parties.

The creation of a think tank can help to incubate and accelerate differentiated programmes to tackle the transition to a circular economy. The ambition is to create a dynamic in which willing actors from different levels can start to strategise together with others and find the right parties to discuss with.

Spaces in transition

9. Exploring current circular spaces and imagining future ones

Exploring and imagining the future spaces that facilitate circular strategies and activities is crucial to implement circularity in our environment. These spaces are places where new conditions are created based on changing frameworks, legislation, activities, clusters, etc. In addition, thinking about space, both in concrete sites and as a research tool, helps to translate abstract targets into specific space-related elements.

If a pilot project on a specific site is successful, the knowledge and working methods can be transferred to a more general strategy, accelerating the transition. The spatial design, its interrelationship with its environment and its spatial role in a larger plan for the port, city and region are currently unclear. Spatial planners and designers need to be given the opportunity and also guided and challenged to think about these spaces, in combination with other (economic) experts.

The Building Blocks are a first stepping stone to imagine these spaces, where the different conclusions of the Circular (City) Ports exploratory trajectory on legislation, specific projects, the interrelationship between port, city and hinterland, etc. are combined in an imaginary space.

The same exercise should be carried out at other scales: development of circular areas, cluster areas in ports, specific urban economies as a link between port and city, regional plans to connect circular hotspots along waterways, etc. Imagining these areas also makes it possible to broaden the discussion on the circular economy: talking to a wider public about circularity will be more convincing with concrete images and plans. It will show the value of productivity close to where people live and try to facilitate a mental shift.

These new spaces for circularity will definitely have a place in people’s environment, and creating imaginaries can help to open the discussion and change the culture of how these things are seen: from the current negative connotation to a positive one.

10. Mapping unused, underused and degenerating land to initiate new circular dynamics

An overview is needed of this types of spaces where new circular dynamics can be initiated. First, existing vacant spaces in ports, cities and regions should be inventoried and considered as crucial potential spaces where new activities can take place.

These activities should play a role in filling a gap in the surrounding ecosystem or be an important place to start a new dynamic. One example is the construction of a logistics centre in an urban port area as a hinge between the port and the city. Secondly, an inventory of old industries or infrastructures that could be valid for the new economy is needed.

On the one hand, this should prevent the unnecessary demolition of infrastructure that is still useful, such as the reuse of old oil tanks for biofuels. On the other hand, initiatives could be better clustered and positioned. For example, ports are investing in new quays for deep-sea vessels, while activities at existing quays may be declining.

Investment could then be directed to other important projects. These types of areas could be used for pilot projects and as testing grounds to experiment with new legislation, modernised concession policies, new spatial design, circular development, etc. As a testing ground, the recurring questions and opportunities of (re)development are also a learning process: the (re)development with a circular mindset and the general learning from the experiment could be a leverage to start new projects elsewhere. It is important that this indexation does not only take place within the boundaries of the port, but also beyond, looking more at the corridor scale.

11. Design more agile and adaptable planning capabilities

In addition to the mapping of vacant and reusable land, an overview of the different specific planning conditions is needed.

Firstly, planning tools should be inventoried to find out which can be used or redefined in a flexible way to facilitate new circular activities in the port and city. These should support productive activities and protect them from real estate and public pressure. Better coordination between economic expansion (business demand), available space and how this matches up with leases is one example worth exploring.

Secondly, good examples of planning for economic mix in port and city port areas should be highlighted as learning opportunities.

Finally, specific spatial planning that touches the different scales of circularity in ports – company, city port, port region and the delta as a whole – should be studied or initiated with different hotspots in the hinterland.

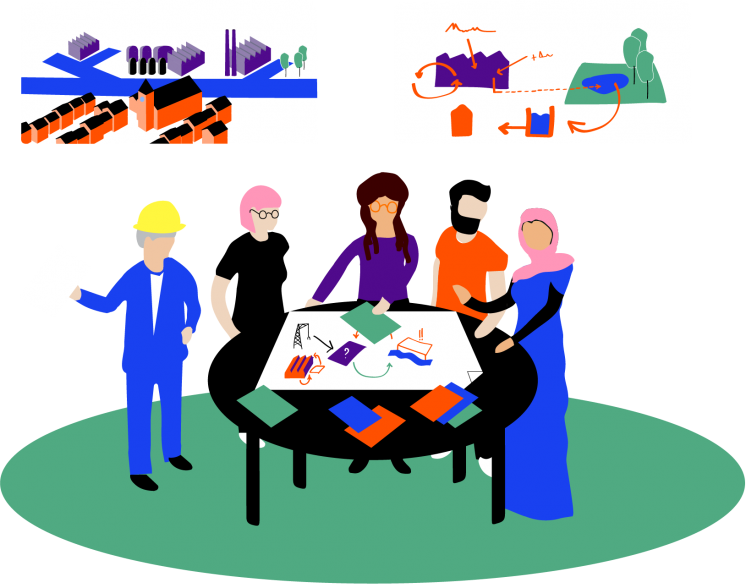

12. Addressing circularity with a multidisciplinary team, including spatial thinkers

For each next step that needs to be taken in the circular economy, it is important to consistently involve spatial experts in the discussion. In fact, a multidisciplinary team with economic, financial, legal, environmental, spatial and other expertise should always be considered when developing new activities and initiatives.

This should be done at all stages of implementing circularity in our current ecosystems: from experimentation and start-up to up-scaling, from specific sites to a master plan for a wider region, from regional visions to the national or European level.

Spatial thinkers can provide concrete material for discussion with other experts, but also with local stakeholders. Creating spatial imaginaries will help to change the culture of looking at things, also for the spatial thinkers themselves. As spatial thinkers, there is a need to explore new instrumental tools to think not only about housing and cultural buildings, but also about industries, productive activities, logistics, etc.

AGENDA SETTING

Joint formulation of next steps

The lessons learnt from the Circular (City) Ports track were synthesised and translated into strategic opportunities that can be exploited by different port and government actors.

The exploration thus shifted from merely documenting and collecting the knowledge, bundled in the various documents of Lessons Learned, Workbook 1 and 2 (Exploration), to a more structured approach by initiating strategic thinking and valorizing/sharing insights. This shifts the focus from looking only at the scale of the ‘City Port’ to looking more generally at existing and potential ‘Circular Port Projects’.